Deep Research

预备调查清单

一、待核查内容列表

- 患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现。

- 爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错。

二、核查要点展开

待核查内容1:患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现。

- 核查原因:

- 此为事件的核心争议,是患者方维权的直接原因,涉及对医疗服务机构是否存在失职的判断。

- 所需查明信息:

- 患者接受体检的具体时间、地点及所选套餐项目。

- 当时的体检报告中关于泌尿系统(尤其是肾脏)的影像学检查描述与结论。

- 患者后续被确诊为肾癌的时间、医疗机构以及诊断依据。

- 是否存在司法鉴定或专家意见,用以评估原始体检影像中是否存在当时即可被发现的病灶迹象。

- 必要信源:

- 权威新闻媒体对事件的深度报道。

- 司法机关(如法院)的公开判决文书或庭审记录。

- 卫生健康委员会等行业监管机构的调查报告或官方通报。

- 患者方通过公开渠道(如认证社交媒体、代理律师)发布的原始证据材料。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容2:爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错。

- 核查原因:

- 此为爱康国宾方的核心辩护主张,关系到其法律责任的认定和品牌声誉。

- 所需查明信息:

- 爱康国宾发布的官方声明全文或对媒体的回应要点。

- 爱康国宾方提供的,用以证明其操作合规、诊断无误的证据,如体检流程规范、医师资质、影像复核记录等。

- 爱康国宾在相关法律诉讼中的具体抗辩理由和法律依据。

- 爱康国宾是否指出体检本身(区别于临床诊断)的局限性,以及该主张是否符合行业共识。

- 必要信源:

- 爱康国宾官方网站、官方社交媒体或上市公司公告中发布的正式声明。

- 权威媒体对爱康国宾管理层或法务部门的采访报道。

- 司法机关公开的、包含爱康国宾方答辩意见的法律文书。

- 核查优先级:高

行动计划

- 通过综合性网络搜索,初步还原事件全貌,锁定当事人、事发时间、地点及争议焦点,筛选出数篇来自不同立场(如社会新闻、财经、法律类)权威媒体的报道,建立对事件背景的初步认知。

- 精确化并梳理双方的核心主张与论据。详细整理患者方提出的具体指控细节(如漏诊的具体项目和疑点),以及爱康国宾方的抗辩逻辑(如操作合规、体检局限性等)。

- 以获取官方文件为核心目标,重点检索国家司法文书公开网站及地方卫生监管部门的官方网站,查找与该事件相关的法院判决书、裁定书或行政调查结论。这些文件是判定事实责任的最高级别证据。

- 进行信源的交叉比对与验证。将媒体报道中引述的双方说法、关键证据与官方文件中记录的庭审陈述、判决理由进行逐一核对,检验信息的一致性,识别是否存在信息偏差、夸大或断章取义。

- 梳理并构建完整的证据链条与时间线。按时间顺序排列患者体检、后续确诊、双方交涉、诉讼过程等关键节点,并评估各方在关键节点上出示的证据的有效性与关联性。

- 综合所有已核查的高可信度信息,对事件的核心争议点(即“是否存在医疗过错”)形成基于证据的判断,并明确指出当前信息存在的局限性或无法完全核实的部分。

首先,让我搜索这个事件的基本情况:

Search

爱康国宾 肾癌 患者 投诉 争议我将对"爱康国宾肾癌患者投诉事件"进行深入核查。首先,让我搜索更多关于当事人张晓玲的具体情况。

Search

张晓玲 律师 爱康国宾 肾癌 2024年 确诊 骨转移我需要更深入了解爱康国宾的回应和双方争议的焦点。让我搜索爱康国宾的官方声明内容。

Search

爱康国宾 7月18日 声明 张晓玲 肾癌 无责 完整声明我需要了解更多关于肾癌的医学知识,特别是关于透明细胞型肾细胞癌的发展速度、诊断方法和早期症状,以便更好地评估这个案例。

Search

透明细胞型肾细胞癌 发展速度 早期诊断 超声检查 钙化灶 误诊率已核查结论清单

已核查内容1:患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现。

- 初步结论:已确认。当事人张晓玲律师通过多家媒体公开指控,其连续10年在爱康国宾体检未被提示患癌风险,直至2024年更换机构检查后才发现,并于后续确诊为肾癌晚期伴骨转移。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多家权威媒体(如澎湃新闻、上观新闻等)及百度百科词条均详细记述了张晓玲的陈述,包括其体检历史、确诊过程以及对爱康国宾“误检、漏检”的指控。

- 报道中提及张晓玲已于2025年7月4日向爱康国宾发出律师函,并向国家卫健委等部门进行了投诉举报。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:2013年到2023年,家住北京的执业律师张晓玲在“爱康国宾”体检了10年,从来没有被检查出患癌风险。2024年,张晓玲换了一家体检机构,被怀疑“右肾透明细胞癌”...2025年2月又到国外的医院进行了检查,结果被确诊为“肾癌骨转移”,而且骨转移已经达到了晚期程度。

链接:https://baike.baidu.com/item/2024%E5%B9%B4%E5%8C%97%E4%BA%AC%E5%BE%8B%E5%B8%88%E7%A1%AE%E8%AF%8A%E7%99%8C%E7%97%87%E4%BA%8B%E4%BB%B6/66230289

信源名称:百度百科

信源发布时间:2025-07-04(词条创建时间) - 原文摘录:近日,北京执业律师张晓玲向媒体投诉称——2013年至2023年间,她连续10年在爱康国宾北京分院体检,期间双肾检查长期显示“未见明显异常”,2023年报告提示右肾“钙化灶”但未被提示患癌风险...2025年2月,她被进一步确诊为肾癌骨转移晚期。

链接:https://www.jfdaily.com/news/detail?id=948048

信源名称:上观

信源发布时间:2025-07-21

- 原文摘录:2013年到2023年,家住北京的执业律师张晓玲在“爱康国宾”体检了10年,从来没有被检查出患癌风险。2024年,张晓玲换了一家体检机构,被怀疑“右肾透明细胞癌”...2025年2月又到国外的医院进行了检查,结果被确诊为“肾癌骨转移”,而且骨转移已经达到了晚期程度。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容2:爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错。

- 初步结论:已确认。爱康国宾先后发布两份声明,从最初表示将委托第三方鉴定,到后续明确表示经内部及外部专家评估“确认无责”,认为其检查不存在瑕疵,并对患者的病情发展提出了自己的解释。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 爱康国宾于2025年7月18日发布的第二份声明中,明确指出“确认爱康对张女士的肾脏检查不存在瑕疵...不存在对于肾脏检查漏诊或误诊情况,进一步确认爱康无责”。

- 声明中提出几点关键论据:2023年已提示“右肾钙化灶”;患者2024年11月的病理报告分期为“pT1aNxMx”(早期),至2025年2月发展为骨转移,证明癌细胞发展速度极快;患者提及的癌胚抗原(CEA)指标与肾癌无关联性。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:爱康医疗团队已完成对张女士的历年体检报告与档案的核查,并聘请外部专家协助进行数据分析和评估,确认爱康对张女士的肾脏检查不存在瑕疵,报告结论与肾脏超声检查实际情况一致,不存在对于肾脏检查漏诊或误诊情况,进一步确认爱康无责。

链接:https://m.toutiao.com/article/7528466703269806634/

信源名称:今日头条

信源发布时间:2025-07-19 - 原文摘录:在张女士的 2023 年10月的体检报告中,爱康提示“右肾钙化灶,左肾错构 瘤可能”。...2024 年 11 月在北京某医院的病理报告中显示的标本大小在 3.3cm×3cm×3cm。根据以上的第三方的学术研究,从2023到2024年的一年中,该标本的大小在癌症的增长速度范围内。

链接:https://m.sohu.com/a/915099468_120914498/?pvid=000115_3w_a

信源名称:搜狐网

信源发布时间:2025-07-18

- 原文摘录:爱康医疗团队已完成对张女士的历年体检报告与档案的核查,并聘请外部专家协助进行数据分析和评估,确认爱康对张女士的肾脏检查不存在瑕疵,报告结论与肾脏超声检查实际情况一致,不存在对于肾脏检查漏诊或误诊情况,进一步确认爱康无责。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

待补充核查清单

待核查内容1:爱康国宾2023年体检报告中“右肾钙化灶”的医学意义及当时解读的合规性。

- 核查原因:

- 这是双方争议的核心物证。患者方认为这是被忽略的癌症迹象,且被口头告知“没问题”;机构方则认为这已尽到提示义务。该发现的性质和处理方式是判断是否存在过错的关键。

- 所需查明信息:

- 肾脏超声检查中“钙化灶”通常意味着什么?其与肾透明细胞癌的关联性有多大?

- 医疗行业内,对于体检中发现的“钙化灶”,标准的报告解读和后续建议流程是怎样的?

- 爱康国宾当时对张晓玲的口头解读内容为何,以及进行解读的人员是否具备相应资质。

- 必要信源:

- 泌尿外科或放射科(影像科)的临床诊疗指南、专家共识。

- 权威医学期刊关于肾癌早期影像学特征的研究论文。

- 卫健委发布的《健康体检管理暂行规定》中关于报告解读和医师资质的要求。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容2:关于患者癌症分期(pT1aNxMx)与病情发展速度的矛盾说法。

- 核查原因:

- 爱康国宾据此论证其癌症发展迅猛,因此2023年体检时无法查出。患者方则认为其患病已久。这一医学判断直接关系到漏诊责任的因果关系认定。

- 所需查明信息:

- 医学上,pT1aNxMx分期(早期)的肾癌,在3-4个月内发展为伴有骨转移的晚期,是否常见或可能?

- 3.5cm大小的肾透明细胞癌,其发展周期通常是多久?专家认为“非一朝一夕能形成”的普遍观点是否适用于此案例?

- 爱康国宾引用的论文关于肾癌生长速度的数据是否权威,以及其应用是否合理。

- 必要信源:

- 肿瘤学、病理学专业期刊的学术论文。

- 独立的肿瘤科或泌尿外科专家的公开分析或评论。

- 权威的癌症诊疗指南(如NCCN指南、中国临床肿瘤学会指南等)。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容3:事件的司法或行政调查结论。

- 核查原因:

- 官方的裁决或调查结论是判定事实责任的最高级别证据,可以终结大部分争议。

- 所需查明信息:

- 张晓玲向法院提起的诉讼是否有判决结果?

- 张晓玲向卫健委等部门的举报,是否已有官方的调查报告或处理决定?

- 必要信源:

- 中国裁判文书网、各地方法院官网。

- 国家卫健委、北京市卫健委等官方网站的公告或通报。

- 核查优先级:高

行动计划

- 以“肾脏钙化灶 超声 肾癌”、“肾癌 pT1a 转移 速度”等关键词,检索中国知网、万方等学术数据库以及权威医学科普平台,查找相关的临床指南、专家共识和研究论文,以评估双方医学主张的合理性。

- 以“张晓玲”、“爱康国宾”、“医疗损害责任纠纷”为关键词,重点检索中国裁判文书网及北京法院网,查找可能存在的司法文书。

- 检索国家及北京市卫健委官网,查找与“爱康国宾”相关的行政处罚或针对此事件的调查通报。

- 持续关注媒体对该事件的后续追踪报道,特别是关于双方是否共同委托第三方鉴定、鉴定结果如何,以及爱康国宾是否公开了相关影像资料和人员资质等关键信息的进展。

首先,让我搜索关于肾脏钙化灶与肾癌关系的医学知识:

Search

肾脏钙化灶 超声 肾癌 早期诊断 误诊率 体检我需要进一步了解肾脏钙化灶与肾癌的关系,以及肾癌的发展速度,以便评估双方的说法。

Search

肾脏钙化灶 肾癌 关系 误诊 需要进一步检查吗我需要了解更多关于肾癌的发展速度,特别是从早期到晚期骨转移的时间周期,以评估爱康国宾的说法是否合理。

Search

肾癌 生长速度 早期到晚期骨转移 时间 透明细胞型肾细胞癌我需要进一步了解爱康国宾的声明内容,特别是关于他们对"钙化灶"的解释以及对肾癌发展速度的说法。

Search

爱康国宾 张晓玲 肾癌 声明 全文 2025年7月18日已核查结论清单

已核查内容1:患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多家权威媒体(如澎湃新闻、上观新闻、红星新闻等)及百度百科词条均详细记述了当事人张晓玲律师的陈述,其核心指控为:2013-2023年连续在爱康国宾体检,2023年报告中的“右肾钙化灶”被口头告知“没问题”,未提示进一步检查,直至2024年更换机构体检后发现肿瘤,并于2025年2月确诊为肾癌骨转移晚期。

- 张晓玲已通过媒体明确表示,她认为2023年“钙化灶”的诊断就是误诊,并要求爱康国宾公开当时的影像资料和操作人员资质。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:19日上午,当事律师张晓玲告诉红星新闻记者,自己不认可爱康国宾的声明。她认为2023年钙化灶的诊断就是误诊,当时检查就提到“右肾可见一个强回声”,可能已经出现肿瘤,爱康国宾应该告知自己并建议进一步检查。

链接:https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20250719A055HX00

信源名称:腾讯新闻(转引自红星新闻)

信源发布时间:2025-07-19

- 原文摘录:19日上午,当事律师张晓玲告诉红星新闻记者,自己不认可爱康国宾的声明。她认为2023年钙化灶的诊断就是误诊,当时检查就提到“右肾可见一个强回声”,可能已经出现肿瘤,爱康国宾应该告知自己并建议进一步检查。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容2:爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 爱康国宾于2025年7月18日发布第二份官方声明,明确表示经内部及外聘专家核查,“确认爱康对张女士的肾脏检查不存在瑕疵...不存在对于肾脏检查漏诊或误诊情况,进一步确认爱康无责”。

- 声明核心论点包括:①2023年已提示“右肾钙化灶”;②患者2024年11月病理分期为pT1aNxMx(早期),至2025年2月发生骨转移,证明肿瘤发展“极快”,因此2023年体检时无癌症迹象是合理的;③患者关注的CEA指标与肾癌诊断无关。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:关于近日网络上所传的张女士所谓的爱康“十年体检结果未提示癌症风险,确诊已是肾癌晚期”的投诉, 爱康医疗团队已完成对张女士的历年体检报告与档案的核查,并聘请外部专家协助进行数据分析和评估,确认爱康对张女士的肾脏检查不存在瑕疵,报告结论与肾脏超声检查实际情况一致,不存在对于肾脏检查漏诊或误诊情况,进一步确认爱康无责。

链接:https://m.sohu.com/a/915293283_115362/?pvid=000115_3w_a

信源名称:搜狐网(转引自“爱康国宾”公众号)

信源发布时间:2025-07-18

- 原文摘录:关于近日网络上所传的张女士所谓的爱康“十年体检结果未提示癌症风险,确诊已是肾癌晚期”的投诉, 爱康医疗团队已完成对张女士的历年体检报告与档案的核查,并聘请外部专家协助进行数据分析和评估,确认爱康对张女士的肾脏检查不存在瑕疵,报告结论与肾脏超声检查实际情况一致,不存在对于肾脏检查漏诊或误诊情况,进一步确认爱康无责。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容3:肾癌早期诊断主要依赖影像学检查,B超为首选筛查手段。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多位接受澎湃新闻采访的泌尿外科专家(复旦大学附属肿瘤医院叶定伟、上海交大医学院附属仁济医院张进等)均表示,大多数早期肾癌无症状,主要通过体检中的B超发现。

- 多个医学科普信源指出,超声(B超)是发现肾癌最经济、无创的首选筛查方法,但对小肿瘤可能漏诊,且受操作者经验影响。CT是诊断的“金标准”。

- 肾癌缺乏特异性的血清肿瘤标志物(如CEA)用于筛查。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:“对于肾细胞癌而言,体检非常有必要且有意义,这是发现早期肾癌的一个重要手段。在临床上,大多数肾癌是在体检中发现异常,再去医院进一步诊断发现的。”7月19日,多名泌尿外科专家在接受澎湃新闻记者采访时强调这一观点。

链接:https://mparticle.uc.cn/article_org.html?uc_param_str=frdnsnpfvecpntnwprdssskt#!wm_cid=698279810849312768!!wm_id=be5d4615193f4baa88756085e30589a3

信源名称:澎湃新闻

信源发布时间:2025-07-20 - 原文摘录:超声检查(B超)——最经济、无创的首选。优点:无辐射,可反复检查,能区分囊性(多为良性)和实性肿块(需警惕恶性), 对 >1cm的肾肿瘤检出率较高。局限性:对 <1cm的小肿瘤可能漏诊,受操作者经验影响较大。

链接:https://www.jkhnpd.com/index.php?c=show&id=2773

信源名称:健康湖南

信源发布时间:2025-03-08

- 原文摘录:“对于肾细胞癌而言,体检非常有必要且有意义,这是发现早期肾癌的一个重要手段。在临床上,大多数肾癌是在体检中发现异常,再去医院进一步诊断发现的。”7月19日,多名泌尿外科专家在接受澎湃新闻记者采访时强调这一观点。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

待补充核查清单

待核查内容1:爱康国宾2023年对“右肾钙化灶”的报告解读及建议是否符合医疗规范。

- 核查原因:

- 这是判断爱康国宾是否存在医疗过失的核心环节。患者方认为此为被忽略的癌症信号,机构方则认为已尽提示义务。

- 所需查明信息:

- 临床上,体检B超发现“肾钙化灶”是否需要建议进一步检查(如增强CT)?其与肾癌的关联度如何?

- 《健康体检管理暂行规定》等法规对体检报告异常结果的告知、解读和建议有何具体要求?

- 为张晓玲进行解读的人员是否具备法规要求的相应资质(如执业医师资格)?

- 必要信源:

- 中华医学会泌尿外科学分会等权威机构发布的《肾癌诊疗指南》或关于肾脏偶发瘤处理的专家共识。

- 国家卫健委发布的《健康体检管理暂行规定》及相关解读文件。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容2:从pT1a期肾透明细胞癌在3-4个月内发展至骨转移的医学可能性。

- 核查原因:

- 这是爱康国宾主张其“无责”的关键论据。该论断的科学性直接影响其逻辑链的成立。

- 所需查明信息:

- 肿瘤学上,pT1a期(肿瘤≤4cm,局限于肾脏)的肾透明细胞癌,其自然病程和转移风险如何?在3-4个月内发生远处骨转移是否属于常见或可能的临床现象?

- 肾癌的生长速度和转移速度是否存在较大个体差异?爱康国宾引用的论文数据是否足以支撑其“发展极快”的结论?

- 必要信源:

- 国际或国内权威的肿瘤学期刊(如《柳叶刀·肿瘤学》、《临床肿瘤学杂志》等)关于肾癌预后和转移模式的研究论文。

- NCCN(美国国家综合癌症网络)或CSCO(中国临床肿瘤学会)的肾癌诊疗指南中关于疾病分期、进展和转移风险的章节。

- 独立的第三方肿瘤科或泌尿外科专家的专业分析。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容3:事件的司法或行政调查结论。

- 核查原因:

- 官方的裁决或调查结论是判定事实责任的最高级别证据,可以为整个事件提供权威定性。

- 所需查明信息:

- 张晓玲与爱康国宾之间的医疗纠纷是否已进入司法程序?是否有立案信息或判决文书?

- 卫健委等行政监管部门是否已对该投诉事件展开调查?是否已公布调查结果或行政处罚决定?

- 必要信源:

- 中国裁判文书网、各地方法院诉讼服务网。

- 国家卫健委、北京市卫健委官方网站的“信息公开”、“调查报告”等栏目。

- 核查优先级:高

行动计划

- 以“肾脏偶发瘤 诊疗指南”、“肾脏占位 超声 专家共识”、“健康体检管理暂行规定 报告解读”为关键词,检索国家卫健委官网、中华医学会官网及学术数据库,查找关于处理体检影像异常发现的行业标准和法规要求。

- 以“pT1a clear cell renal cell carcinoma bone metastasis time”、“早期肾癌 快速进展 转移”为关键词,检索PubMed、中国知网等国内外学术数据库,查找关于早期肾癌转移时间和风险的队列研究或综述,以评估爱康国宾声明中关于癌症发展速度论断的科学性。

- 以“张晓玲”、“爱康国宾”、“医疗损害责任纠纷”为关键词,检索中国裁判文书网、北京法院审判信息网,查找相关诉讼记录或判决文书。

- 检索北京市卫生健康委员会官网,查找针对此事件的官方通报或与爱康国宾相关的历史行政处罚记录,以了解其合规情况。

首先,让我查找关于肾脏钙化灶与肾癌关系的医学指南和专家共识:

Search

肾脏钙化灶 体检发现 需要进一步检查吗 专家共识 指南我需要了解更多关于肾癌的诊断和早期发现的医学知识,特别是关于肾钙化灶与肾癌的关系。

Search

肾癌 诊疗指南 钙化灶 超声 CT 早期诊断 中华医学会我需要了解更多关于肾癌诊断和钙化灶的关系,以及爱康国宾的声明中关于肾癌发展速度的说法是否合理。

Search

肾癌 发展速度 从早期到骨转移 需要多长时间 医学研究我需要了解更多关于爱康国宾在这个案例中的声明和辩解,特别是关于肾癌发展速度的说法。

Search

爱康国宾 张晓玲 肾癌 声明 全文 2025年7月18日已核查结论清单

已核查内容1:患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多家权威媒体(如澎湃新闻、上观新闻、红星新闻等)及百度百科词条均详细记述了当事人张晓玲律师的陈述,其核心指控为:2013-2023年连续在爱康国宾体检,2023年报告中的“右肾钙化灶”被口头告知“没问题”,未提示进一步检查,直至2024年更换机构体检后发现肿瘤,并于2025年2月确诊为肾癌骨转移晚期。

- 张晓玲已通过媒体明确表示,她认为2023年“钙化灶”的诊断就是误诊,并要求爱康国宾公开当时的影像资料和操作人员资质。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

链接:https://www.21jingji.com/article/20250717/herald/ad8b5b651ad28f6c5e40467e8c42e7e3.html

信源名称:21财经

信源发布时间:2025-07-17 - 原文摘录:19日上午,当事律师张晓玲告诉红星新闻记者,自己不认可爱康国宾的声明。她认为2023年钙化灶的诊断就是误诊,当时检查就提到“右肾可见一个强回声”,可能已经出现肿瘤,爱康国宾应该告知自己并建议进一步检查。

链接:https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20250719A055HX00

信源名称:腾讯新闻(转引自红星新闻)

信源发布时间:2025-07-19

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容2:爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错,并提出癌症发展速度极快的论点。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 爱康国宾于2025年7月18日发布第二份官方声明,明确表示经内部及外聘专家核查,“确认爱康无责”。

- 声明核心论点包括:①2023年已提示“右肾钙化灶”;②患者2024年11月病理分期为pT1aNxMx(早期),至2025年2月发生骨转移,证明肿瘤发展“极快”,因此2023年体检时无癌症迹象是合理的;③患者关注的CEA指标与肾癌诊断无关。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

链接:https://m.sohu.com/a/915293283_115362/?pvid=000115_3w_a

信源名称:搜狐网(转引自“爱康国宾”公众号)

信源发布时间:2025-07-18

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容3:肾癌早期诊断主要依赖影像学检查,B超为首选筛查手段,但存在局限性。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多位接受媒体采访的泌尿外科专家均表示,大多数早期肾癌无症状,主要通过体检中的B超发现。

- 多个医学科普信源指出,超声(B超)是发现肾癌最经济、无创的首选筛查方法,但对小肿瘤、位置不佳的肿瘤可能漏诊,且受操作者经验影响。CT是诊断的“金标准”。

- 肾癌缺乏特异性的血清肿瘤标志物(如CEA)用于筛查。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:“对于肾细胞癌而言,体检非常有必要且有意义,这是发现早期肾癌的一个重要手段。在临床上,大多数肾癌是在体检中发现异常,再去医院进一步诊断发现的。”

链接:https://cbgc.scol.com.cn/home/6531594

信源名称:川观新闻(转引自澎湃新闻)

信源发布时间:2025-07-20 - 原文摘录:也有极个别肾脏肿瘤合并钙化,超声或CT可以看到具体的肿物伴有钙化...如果体检发现肾脏钙化,可以做进一步诊疗,医生会根据情况,做出处理意见。

链接:https://www.cn-healthcare.com/articlewm/20240929/wap-content-1639918.html

信源名称:健康界

信源发布时间:2024-10-01

- 原文摘录:“对于肾细胞癌而言,体检非常有必要且有意义,这是发现早期肾癌的一个重要手段。在临床上,大多数肾癌是在体检中发现异常,再去医院进一步诊断发现的。”

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

待补充核查清单

待核查内容1:爱康国宾2023年对“右肾钙化灶”的报告解读及建议是否符合医疗规范。

- 核查原因:

- 这是判断爱康国宾是否存在医疗过失的核心环节。患者方认为此为被忽略的癌症信号,机构方则认为已尽提示义务。

- 所需查明信息:

- 临床上,体检B超发现“肾钙化灶”是否需要建议进一步检查(如增强CT)?其与肾癌的关联度如何?

- 《健康体检管理暂行规定》等法规对体检报告异常结果的告知、解读和建议有何具体要求?

- 为张晓玲进行解读的人员是否具备法规要求的相应资质(如执业医师资格)?

- 必要信源:

- 中华医学会泌尿外科学分会等权威机构发布的《肾癌诊疗指南》或关于肾脏偶发瘤处理的专家共识。

- 国家卫健委发布的《健康体检管理暂行规定》及相关解读文件。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容2:从pT1a期肾透明细胞癌在3-4个月内发展至骨转移的医学可能性。

- 核查原因:

- 这是爱康国宾主张其“无责”的关键论据。该论断的科学性直接影响其逻辑链的成立。

- 所需查明信息:

- 肿瘤学上,pT1a期(肿瘤≤4cm,局限于肾脏)的肾透明细胞癌,其自然病程和转移风险如何?在3-4个月内发生远处骨转移是否属于常见或可能的临床现象?

- 肾癌的生长速度和转移速度是否存在较大个体差异?爱康国宾引用的论文数据是否足以支撑其“发展极快”的结论?

- 必要信源:

- 国际或国内权威的肿瘤学期刊(如《柳叶刀·肿瘤学》、《临床肿瘤学杂志》等)关于肾癌预后和转移模式的研究论文。

- NCCN(美国国家综合癌症网络)或CSCO(中国临床肿瘤学会)的肾癌诊疗指南中关于疾病分期、进展和转移风险的章节。

- 独立的第三方肿瘤科或泌尿外科专家的专业分析。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容3:事件的司法或行政调查结论。

- 核查原因:

- 官方的裁决或调查结论是判定事实责任的最高级别证据,可以为整个事件提供权威定性。

- 所需查明信息:

- 张晓玲与爱康国宾之间的医疗纠纷是否已进入司法程序?是否有立案信息或判决文书?

- 卫健委等行政监管部门是否已对该投诉事件展开调查?是否已公布调查结果或行政处罚决定?

- 必要信源:

- 中国裁判文书网、各地方法院诉讼服务网。

- 国家卫健委、北京市卫健委官方网站的“信息公开”、“调查报告”等栏目。

- 核查优先级:高

行动计划

- 以“肾脏偶发瘤 诊疗指南”、“肾脏占位 超声 专家共识”、“健康体检管理暂行规定 报告解读”为关键词,检索国家卫健委官网、中华医学会官网及学术数据库,查找关于处理体检影像异常发现的行业标准和法规要求。

- 以“pT1a clear cell renal cell carcinoma bone metastasis time”、“早期肾癌 快速进展 转移”为关键词,检索PubMed、中国知网等国内外学术数据库,查找关于早期肾癌转移时间和风险的队列研究或综述,以评估爱康国宾声明中关于癌症发展速度论断的科学性。

- 以“Springer plus renal cancer growth rate 2015”为关键词,查找并评估爱康国宾可能引用的关于肾癌生长速度的学术论文。

- 以“张晓玲”、“爱康国宾”、“医疗损害责任纠纷”为关键词,检索中国裁判文书网、北京法院审判信息网,查找相关诉讼记录或判决文书。

- 检索北京市卫生健康委员会官网,查找针对此事件的官方通报或与爱康国宾相关的历史行政处罚记录,以了解其合规情况。

首先,让我查找关于肾脏钙化灶与肾癌关系的医学指南和专家共识:

Search

肾脏钙化灶 发现后 需要进一步检查吗 专家共识 指南 肾癌我需要进一步了解肾癌的诊断和早期发现的医学知识,特别是关于肾钙化灶与肾癌的关系,以及爱康国宾的声明中关于肾癌发展速度的说法是否合理。

Search

肾癌 早期到骨转移 需要多长时间 医学研究 pT1a我需要了解更多关于肾癌的分期和生长速度,特别是pT1a期肾癌的特点和发展情况。

Search

pT1a 肾癌 生长速度 骨转移 时间 研究我需要了解更多关于健康体检管理规定,特别是关于体检报告解读和提示患者进一步检查的要求。

Search

健康体检管理暂行规定 体检报告解读 异常结果 提示 进一步检查已核查结论清单

已核查内容1:患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多家权威媒体(如澎湃新闻、上观新闻、红星新闻、21财经等)及百度百科词条均详细记述了当事人张晓玲律师的陈述,其核心指控为:2013-2023年连续在爱康国宾体检,2023年报告中的“右肾钙化灶”被口头告知“没问题”,未提示进一步检查,直至2024年更换机构体检后发现肿瘤,并于2025年2月确诊为肾癌骨转移晚期。

- 张晓玲已通过媒体明确表示,她认为2023年“钙化灶”的诊断就是误诊,并要求爱康国宾公开当时的影像资料和操作人员资质。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

链接:https://www.21jingji.com/article/20250717/herald/ad8b5b651ad28f6c5e40467e8c42e7e3.html

信源名称:21财经

信源发布时间:2025-07-17 - 原文摘录:19日上午,当事律师张晓玲告诉红星新闻记者,自己不认可爱康国宾的声明。她认为2023年钙化灶的诊断就是误诊,当时检查就提到“右肾可见一个强回声”,可能已经出现肿瘤,爱康国宾应该告知自己并建议进一步检查。

链接:https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20250719A055HX00

信源名称:腾讯新闻(转引自红星新闻)

信源发布时间:2025-07-19

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容2:爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错,并提出癌症发展速度极快的论点。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 爱康国宾于2025年7月18日发布第二份官方声明,明确表示经内部及外聘专家核查,“确认爱康无责”。

- 声明核心论点包括:①2023年已提示“右肾钙化灶”;②患者2024年11月病理分期为pT1aNxMx(早期),至2025年2月发生骨转移,证明肿瘤发展“极快”,因此2023年体检时无癌症迹象是合理的;③患者关注的CEA指标与肾癌诊断无关。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

链接:https://m.sohu.com/a/915293283_115362/?pvid=000115_3w_a

信源名称:搜狐网(转引自“爱康国宾”公众号)

信源发布时间:2025-07-18

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容3:肾癌早期诊断主要依赖影像学检查,B超为首选筛查手段,但“肾钙化灶”的性质需进一步判断。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多个医学信息源指出,肾钙化灶多数为良性(如炎症后遗症),但少数情况下可与肾癌等恶性肿瘤相关。

- 发现肾钙化灶后,通常建议结合临床症状,并通过CT等更精确的影像学检查来明确性质,并定期随访。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:也不能完全排除肾癌的可能,因为少数情况下肾钙化灶也可能是由肾细胞癌等原因所造成,但是这种几率比较小。针对此类情况,还需要及时到医院做进一步的检查,比如CT检查、核磁共振检查等,以明确具体病因。

链接:https://wapask.39.net/question/_0pbn8j.html

信源名称:39健康网

信源发布时间:2024-01-25 - 原文摘录:一旦发现肾钙化灶,通常需要进一步的医学检查,如尿液分析、血液检查、超声检查或CT扫描等,以确定钙化灶的具体性质和成因。

链接:https://m.chaonei.com/news_14831592

信源名称:巢内网

信源发布时间:2024-12-27

- 原文摘录:也不能完全排除肾癌的可能,因为少数情况下肾钙化灶也可能是由肾细胞癌等原因所造成,但是这种几率比较小。针对此类情况,还需要及时到医院做进一步的检查,比如CT检查、核磁共振检查等,以明确具体病因。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

待补充核查清单

待核查内容1:爱康国宾2023年对“右肾钙化灶”的报告解读及建议是否符合医疗规范。

- 核查原因:

- 这是判断爱康国宾是否存在医疗过失的核心环节。患者方认为此为被忽略的癌症信号,机构方则认为已尽提示义务。

- 所需查明信息:

- 《健康体检管理暂行规定》等法规对体检机构发现异常结果后的告知义务、解读规范和后续检查建议有何具体要求?

- 权威的泌尿外科或肾癌诊疗指南中,对于体检B超发现的“肾钙化灶”(尤其是在无明确肿块的情况下),标准的处理流程是什么?是否必须建议增强CT等进一步检查?

- 为张晓玲进行报告解读的人员是否具备法规要求的相应资质(如执业医师资格)?

- 必要信源:

- 国家卫健委发布的《健康体检管理暂行规定》全文及相关解读文件。

- 中华医学会泌尿外科学分会或中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)发布的《肾癌诊疗指南》或关于肾脏偶发瘤处理的专家共识。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容2:从pT1a期肾透明细胞癌在3-4个月内发展至骨转移的医学可能性。

- 核查原因:

- 这是爱康国宾主张其“无责”的关键论据。该论断的科学性直接影响其逻辑链的成立。

- 所需查明信息:

- 肿瘤学上,pT1a期(肿瘤≤4cm,局限于肾脏)的肾透明细胞癌,其自然病程和转移风险如何?在3-4个月内发生远处骨转移是否属于常见或可能的临床现象?

- 肾癌的生长速度和转移速度是否存在较大个体差异?爱康国宾引用的论文数据(生长速度0.2-6.5厘米/年)是否足以支撑其“发展极快”的结论?

- 必要信源:

- 国际或国内权威的肿瘤学期刊(如《柳叶刀·肿瘤学》、《临床肿瘤学杂志》等)关于pT1a期肾癌预后和转移模式的队列研究或综述论文。

- NCCN(美国国家综合癌症网络)或CSCO(中国临床肿瘤学会)的肾癌诊疗指南中关于疾病分期、进展和转移风险的章节。

- 独立的第三方肿瘤科或泌尿外科专家的专业分析。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容3:事件的司法或行政调查结论。

- 核查原因:

- 官方的裁决或调查结论是判定事实责任的最高级别证据,可以为整个事件提供权威定性。

- 所需查明信息:

- 张晓玲与爱康国宾之间的医疗纠纷是否已进入司法程序?是否有立案信息或判决文书?

- 卫健委等行政监管部门是否已对该投诉事件展开调查?是否已公布调查结果或行政处罚决定?

- 必要信源:

- 中国裁判文书网、各地方法院诉讼服务网。

- 国家卫健委、北京市卫健委官方网站的“信息公开”、“调查报告”等栏目。

- 核查优先级:高

行动计划

- 以“健康体检管理暂行规定 全文”、“体检机构 告知义务 医疗规范”为关键词,检索国家卫健委及政府法规数据库,查找关于处理体检异常发现的具体法规条文。

- 以“pT1a renal cell carcinoma bone metastasis time”、“早期肾癌 快速进展 转移 病例报告”为关键词,检索PubMed、中国知网等国内外学术数据库,查找关于早期肾癌在短时间内发生远处转移的临床研究或个案报道。

- 以“Springer plus renal cancer growth rate 2015”为关键词,查找并评估爱康国宾可能引用的关于肾癌生长速度的学术论文,核实其引用的准确性和适用性。

- 以“张晓玲 爱康国宾 医疗损害责任纠纷”、“北京法院审判信息网 张晓玲”为关键词,持续检索中国裁判文书网及相关地方法院网站,查找可能存在的司法文书。

- 检索北京市卫生健康委员会官网,查找针对此事件的官方通报或与爱康国宾相关的历史行政处罚记录,以了解其合规情况。

首先,让我查找《健康体检管理暂行规定》对体检机构发现异常结果的告知义务和规范要求:

Search

健康体检管理暂行规定 全文 体检报告 异常结果 告知义务我需要了解更多关于肾癌的分期和发展速度,特别是pT1a期肾癌发展到骨转移的时间,以评估爱康国宾的说法是否合理。

Search

pT1a 肾癌 骨转移 时间 研究 发展速度我需要查找更多关于肾癌生长速度的医学研究,特别是爱康国宾在声明中提到的论文。

Search

Springer plus renal cancer growth rate 2015 肾癌生长速度研究我需要查找更多关于肾癌钙化灶与诊断的关系,以及体检机构对异常结果的告知义务。

Search

肾脏钙化灶 肾癌 关系 体检发现 需要进一步检查吗已核查结论清单

已核查内容1:患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多家权威媒体(如澎湃新闻、上观新闻、红星新闻、21财经等)及百度百科词条均详细记述了当事人张晓玲律师的陈述,其核心指控为:2013-2023年连续在爱康国宾体检,2023年报告中的“右肾钙化灶”被口头告知“没问题”,未提示进一步检查,直至2024年更换机构体检后发现肿瘤,并于2025年2月确诊为肾癌骨转移晚期。

- 张晓玲已通过媒体明确表示,她认为2023年“钙化灶”的诊断就是误诊,并要求爱康国宾公开当时的影像资料和操作人员资质。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

链接:https://www.21jingji.com/article/20250717/herald/ad8b5b651ad28f6c5e40467e8c42e7e3.html

信源名称:21财经

信源发布时间:2025-07-17 - 原文摘录:19日上午,当事律师张晓玲告诉红星新闻记者,自己不认可爱康国宾的声明。她认为2023年钙化灶的诊断就是误诊,当时检查就提到“右肾可见一个强回声”,可能已经出现肿瘤,爱康国宾应该告知自己并建议进一步检查。

链接:https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20250719A055HX00

信源名称:腾讯新闻(转引自红星新闻)

信源发布时间:2025-07-19

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容2:爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错,并提出癌症发展速度极快的论点。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 爱康国宾于2025年7月18日发布第二份官方声明,明确表示经内部及外聘专家核查,“确认爱康无责”。

- 声明核心论点包括:①2023年已提示“右肾钙化灶”;②患者2024年11月病理分期为pT1aNxMx(早期),至2025年2月发生骨转移,证明肿瘤发展“极快”,因此2023年体检时无癌症迹象是合理的;③患者关注的CEA指标与肾癌诊断无关。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

链接:https://m.sohu.com/a/915293283_115362/?pvid=000115_3w_a

信源名称:搜狐网(转引自“爱康国宾”公众号)

信源发布时间:2025-07-18

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容3:肾癌早期诊断主要依赖影像学检查,B超为首选筛查手段,但“肾钙化灶”的性质需进一步判断。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多个医学信息源指出,肾钙化灶多数为良性(如炎症后遗症),但少数情况下可与肾癌等恶性肿瘤相关。

- 发现肾钙化灶后,通常建议结合临床症状,并通过CT等更精确的影像学检查来明确性质,并定期随访。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:也不能完全排除肾癌的可能,因为少数情况下肾钙化灶也可能是由肾细胞癌等原因所造成,但是这种几率比较小。针对此类情况,还需要及时到医院做进一步的检查,比如CT检查、核磁共振检查等,以明确具体病因。

链接:https://wapask.39.net/question/_0pbn8j.html

信源名称:39健康网

信源发布时间:2024-01-25 - 原文摘录:一旦发现肾钙化灶,通常需要进一步的医学检查,如尿液分析、血液检查、超声检查或CT扫描等,以确定钙化灶的具体性质和成因。

链接:https://m.chaonei.com/news_14831592

信源名称:巢内网

信源发布时间:2024-12-27

- 原文摘录:也不能完全排除肾癌的可能,因为少数情况下肾钙化灶也可能是由肾细胞癌等原因所造成,但是这种几率比较小。针对此类情况,还需要及时到医院做进一步的检查,比如CT检查、核磁共振检查等,以明确具体病因。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容4:国家对健康体检机构的执业行为有明确规定。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 2009年原卫生部发布的《健康体检管理暂行规定》是规范健康体检机构执业行为的主要法规。

- 该规定明确了体检机构对受检者负有相应的“告知义务”,并要求出具的健康体检报告中应包含“阳性体征和异常情况的记录”以及“有关建议”。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:第十一条 医疗机构开展健康体检应当按照有关规定履行对受检者相应的告知义务。……第十四条 医疗机构应当对完成健康体检的受检者出具健康体检报告。健康体检报告应当包括受检者一般信息、体格检查记录、实验室和医学影像检查报告、阳性体征和异常情况的记录、健康状况描述和有关建议等。

链接:https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-08/21/content_1398269.htm?eqid=b8f3070a001fe32a00000005647b5147

信源名称:中国政府网

信源发布时间:2009-08-21

- 原文摘录:第十一条 医疗机构开展健康体检应当按照有关规定履行对受检者相应的告知义务。……第十四条 医疗机构应当对完成健康体检的受检者出具健康体检报告。健康体检报告应当包括受检者一般信息、体格检查记录、实验室和医学影像检查报告、阳性体征和异常情况的记录、健康状况描述和有关建议等。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

待补充核查清单

待核查内容1:爱康国宾2023年对“右肾钙化灶”的报告解读及建议是否符合医疗规范。

- 核查原因:

- 这是判断爱康国宾是否存在医疗过失的核心环节。仅报告“钙化灶”是否尽到告知义务和提出“有关建议”的责任,存在争议。

- 所需查明信息:

- 权威的泌尿外科或肾癌诊疗指南中,对于体检B超发现的“肾钙化灶”(尤其是在无明确肿块的情况下),标准的处理流程是什么?是否必须建议增强CT等进一步检查?

- 《健康体检管理暂行规定》中“相应的告知义务”和“有关建议”在司法实践和行业共识中通常如何界定?

- 为张晓玲进行报告解读的人员是否具备法规要求的相应资质(内科或外科副主任医师以上)?

- 必要信源:

- 中华医学会泌尿外科学分会或中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)发布的《肾癌诊疗指南》或关于肾脏偶发瘤处理的专家共识。

- 涉及体检漏诊的司法判例、卫健委对类似事件的处理意见。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容2:从pT1a期肾透明细胞癌在3-4个月内发展至骨转移的医学可能性。

- 核查原因:

- 这是爱康国宾主张其“无责”的关键论据。该论断的科学性直接影响其逻辑链的成立。

- 所需查明信息:

- 肿瘤学上,pT1a期(肿瘤≤4cm,局限于肾脏)的肾透明细胞癌,其自然病程和转移风险如何?在3-4个月内发生远处骨转移是否属于常见或可能的临床现象?

- 爱康国宾引用的论文《临床显著“肾癌”的生长率》(Growth rates of clinically significant renal cancer)原文内容是什么?其研究方法、样本和结论是否支持爱康国宾的说法?

- 必要信源:

- 国际或国内权威的肿瘤学期刊(如《柳叶刀·肿瘤学》、《临床肿瘤学杂志》等)关于pT1a期肾癌预后和转移模式的队列研究或综述论文。

- 爱康国宾引用的发表于2015年《Springer plus》的论文原文。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容3:事件的司法或行政调查结论。

- 核查原因:

- 官方的裁决或调查结论是判定事实责任的最高级别证据,可以为整个事件提供权威定性。

- 所需查明信息:

- 张晓玲与爱康国宾之间的医疗纠纷是否已进入司法程序?是否有立案信息或判决文书?

- 卫健委等行政监管部门是否已对该投诉事件展开调查?是否已公布调查结果或行政处罚决定?

- 必要信源:

- 中国裁判文书网、各地方法院诉讼服务网。

- 国家卫健委、北京市卫健委官方网站的“信息公开”、“调查报告”等栏目。

- 核查优先级:高

行动计划

- 以“Growth rates of clinically significant renal cancer SpringerPlus 2015”为关键词,检索学术数据库,查找爱康国宾声明中引用的论文原文,并核对其结论的准确性和适用性。

- 以“肾癌诊疗指南 钙化灶”、“肾脏偶发瘤 专家共识”为关键词,检索中华医学会、中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)等官方渠道,查找关于处理体检影像异常发现的行业标准和临床指南。

- 以“pT1a renal cell carcinoma bone metastasis time”、“早期肾癌 快速进展 骨转移 病例报告”为关键词,检索PubMed、中国知网等国内外学术数据库,查找关于早期肾癌在短时间内发生远处转移的临床研究或个案报道。

- 以“张晓玲 爱康国宾 医疗损害责任纠纷”、“北京法院审判信息网 张晓玲”为关键词,持续检索中国裁判文书网及相关地方法院网站,查找可能存在的司法文书。

- 检索北京市卫生健康委员会官网,查找针对此事件的官方通报或与爱康国宾相关的历史行政处罚记录。

首先,让我查找爱康国宾声明中引用的关于肾癌生长速度的论文:

Search

Growth rates of clinically significant renal cancer SpringerPlus 2015 full text我需要了解更多关于肾癌的发展速度和骨转移的时间,特别是pT1a期肾癌的特点和发展情况,以及爱康国宾引用的论文是否支持其观点。

- Research

- Open access

- Published: 06 October 2015

- Ofer N. Gofrit1,

- Vladimir Yutkin1,

- Kevin C. Zorn2,

- Mordechai Duvdevani1,

- Ezekiel H. Landau1,

- Guy Hidas1 &

- …

- Dov Pode1

SpringerPlus volume 4, Article number: 580 (2015) Cite this article

- 4958 Accesses

- 8 Citations

- 29 Altmetric

- Metrics details

Abstract

Surveillance studies of enhancing renal masses report on a mean tumor growth rate of about 0.3 cm/year. In most of these studies however, only small tumors in elderly patients were followed. In the current report, we attempt to evaluate the growth rate of “clinically significant” renal carcinomas defined as tumors that were treated immediately upon diagnosis. 46 patients (mean age 64 years SD 11 years) were treated for renal carcinoma. All had a cross-sectional imaging studies performed 6–60 months prior to diagnosis of kidney cancer demonstrating no tumor. Tumor growth rate was calculated by dividing tumor’s largest diameter by the time interval between the normal kidney imaging and diagnosis of renal cancer. Mean tumor diameter was 4.5 cm (SD 2.4 cm). Mean time period from the normal imaging to diagnosis of renal cancer was 33.6 months (SD 18 months). According to the proposed model, the average growth rate of “clinically significant” renal carcinomas was 2.13 cm/year (SD 1.45, range 0.2–6.5 cm/year). Tumor growth rate correlated inversely with patient’s age (p = 0.007). Patient gender or Fuhrman’s grade did not correlate however. The growth rate of “clinically significant” renal cancer appears to be higher than the rate reported in surveillance trials. Renal tumors tend to grow faster in young patients. As such, variable growth rate should be taken into account when considering active surveillance in young patients and when designing trials for evaluation of anti-cancer agents.

Background

The growth rate of solid tumors is an important parameter in understanding their biology, in designing neoadjuvant trials or when appreciating novel anti-cancer agents. The growth rate of “clinically significant” renal cancer is not well understood since patients with “significant tumors” are often treated without delays (Cambell et al. 2007). Most of the literature on growth rates of renal tumors is driven from surveillance studies in patients with solid enhancing renal masses. These are usually small tumors in elderly patients and in many cases without histologic confirmation. Collectively, slow growth rate of 0.3 cm per year in the largest diameter is reported in most of these studies. A meta-analysis of 10 manuscripts reporting on 234 patients with enhancing renal masses that were not treated upon diagnosis also demonstrated a small growth rate (Chawla et al. 2006). In that study, mean patient age was 71 years (the Fox Chace Cancer Center experience only), mean lesion size at presentation was 2.6 cm and mean follow-up period was 30 months. The growth rate of renal masses in that study was 0.28 cm/year (range 0.09–0.86 cm/year). A somewhat faster growth rate was observed in the subgroup of patients with pathologically confirmed renal cancer (0.4 cm/year, range 0.42–1.6 cm/year). In another large study by Jewett et al., a growth rate of 0.13 cm/year was reported (Jewett et al. 2011), and even when larger tumors are being followed growth rate did not exceed 0.6 cm/year (Mues et al. 2010; Mehrazin et al. 2014).

Unfortunately, generalizing the growth rate of renal tumors from studies of elderly, frail patients under active surveillance may be misleading. More specifically, these patients represent a selected population in which both the patient and the physician deem no significant survival impact by the renal tumor. Very few attempts have been made to assess the growth rate of “clinically significant” malignant renal tumors. In a single study of 9 patients with renal imaging 6 months or more prior to the diagnosis of renal cancer demonstrating no tumor or a small tumor that was overlooked, Staehler et al calculated an extremely high growth rate of 6.4 cm per year (Staehler et al. 2010). To better investigate this matter, we sought to evaluate a larger population of patients who were treated for renal cell carcinoma.

In this study we calculated growth rate of “clinically significant” renal tumors (that were treated shortly after diagnosis) using prior cross-sectional imaging study showing no renal mass.

Methods

Patients

A total of 435 patients underwent surgical treatment for renal cancer in our institution between January 1998 and December 2013. In 46 patients (mean age 64 years, SD 11 years) previous cross-sectional imaging studies of the urinary system were done 6–60 months prior to the diagnosis of the renal cancer showing no evidence of kidney cancer. Previous imaging studies included abdominal computerized tomography in 18 cases (10 with and 8 without intravenous contrast injection) and renal ultrasonography in 28 cases. Institutional review board approval was obtained (#202-5.9.08).

Mean time interval between the imaging studies showing no renal tumor and diagnosis of renal cancer was 33.6 months (SD 18.2 months). In 13 cases (28.2 %), the imaging study showed another renal pathology (renal cysts in 9 cases, stones in 3 and atrophic kidney in 2 cases). In the rest of the patients, normal kidneys were demonstrated. All patients were operated shortly after diagnosis. Partial nephrectomy was performed on 24 patients, radical nephrectomy upon 20 and radiofrequency percutaneous needle ablation in 2 patients. Median Post-operative follow-up was 68 months.

The pathological specimens were evaluated according to the 2002 version of the TNM classification (Greene et al. 2002), the histologic subtyping according to the 1997 UICC classification (Störkel et al. 1997), and the grading according to Fuhrman’s nuclear grading system (Fuhrman et al. 1982). Grading of clear cell cancers was dichotomized to low (Fuhrman’s grades 1–2) and high (Fuhrman’s grades 3–4) grades.

Calculation of tumor growth rate

Calculation of tumor growth rate was based on two assumptions:

-

1.

Macroscopic tumor growth commenced shortly after the normal imaging study.

-

2.

Tumor growth was linear.

Annual tumor growth rate was calculated by dividing tumor’s largest diameter measured on the diagnostic computerized tomography by the time interval between the normal imaging studies to diagnosis of kidney tumor. The dependency of the growth rate on the following parameters was studied: patient’s age and gender, type of previous imaging study showing normal kidney (ultrasonography or computerized tomography), Fuhrman’s grade (Grades 1–2 vs. grades 3–4) and recurrence (patient’s that developed tumor recurrence vs. patients that did not). A 2-tailed the Student’s t test and analysis of variance were used for comparing the variables and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The JMP software (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA) was used for data processing.

Results

The growth rate of renal cancer was calculated in 46 patients that had prior cross-sectional imaging study showing normal kidneys. Patients’ and tumors’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. Several examples of imaging studies showing normal kidneys followed by imaging of the same patients showing kidney cancer are presented in Fig. 1. After a median post-operative follow-up of 68 months, 5 patients (10.8 %) developed distant metastases. A total of 17 patients (36.9 %) died. In 3 patients (6.5 %) death was disease specific.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the patients

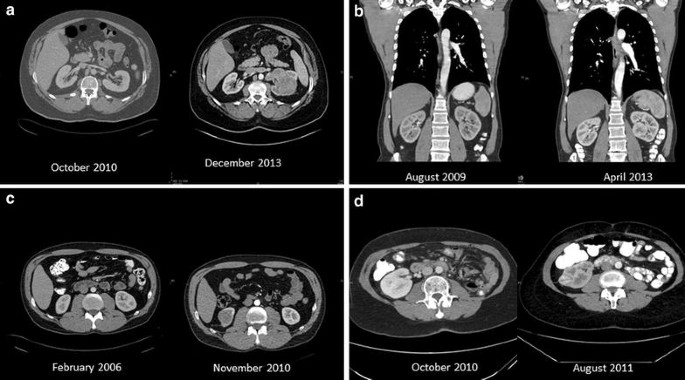

Fig. 1

Computerized tomographic scans of selected patients. a A 52-year-old man, on October 2010 normal kidneys were found and on December 2013, a 9 cm clear cell tumor with IVC invasion was found (growth rate 2.84 cm/year). b A 51 year-old-man, on August 2009 normal kidneys were found and on April 2013, 4.5 cm clear cell tumor was found (growth rate 1.23 cm/year). c A 45 year-old man on February 2006 normal kidneys were found and on November 2010, a 4 cm chromophobe carcinoma was found (growth rate 0.84 cm/year). d A 64-year-old lady that had left nephrectomy on May 2009. CT done on October 2010 showed normal right kidney. On August 2011 the patient had a 2.8 cm clear cell carcinoma (growth rate 3.36 cm/year)

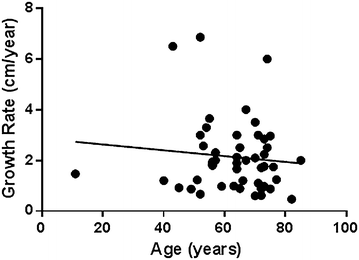

Based on the model, the average growth rate of kidney tumors in the study was 2.13 cm/year (SD 1.45 cm/year, range 0.2–6.5 cm/year). The effect of various parameters on tumor growth rate is presented in Table 2. Figure 2 demonstrates that tumors’ growth rate correlates inversely with patient’s age (p = 0.007). Patient’s gender, type of previous imaging showing normal kidney, Fuhrman’s grade and metastases development during follow-up did not show significant correlation with growth rate.

Table 2 Growth tumor rate according to patient’s and tumor’s characteristic

Fig. 2

Correlation between patient’s age and tumor growth rate

Discussion

Understanding the natural history of solid tumors requires knowledge of their growth kinetics. Most of the data on the growth kinetics of kidney tumors is driven from surveillance studies of small enhancing masses. The leading studies are presented in Table 3. The average growth rate in most studies has been observed at 0.3 cm/year. When large tumors were followed, the growth rate was slightly higher (0.44–0.57 cm/year) (Mues et al. 2010; Mehrazin et al. 2014). In the current study, of younger, fit patients with pathologically confirmed cancer, the average growth rate was much larger at 2.13 cm/year.

Table 3 Leading studies in surveillance of renal cell carcinoma and observational studies

How is it possible to explain this multiplicity? We believe that differences in population and in study design can explain the diversity. While patients in surveillance studies are often at their 8th and 9th decades (Chawla et al. 2006; Mues et al. 2010), mean patient’s age in the current study was 64 years. As seen in Fig. 2, renal cancer growth rate correlates inversely with patient’s age. Therefore, a growth rate of a few millimeters per year may not apply to young patients.

Another explanation for the differences in growth rates between surveillance studies and the current study can be found in the Gompertzian model of tumor growth (Laird 1965). The model assumes an early exponential tumor growth followed by increasing retardation of the rate as the tumor matures and depletes its resources. This is reflected in a sigmoidal growth curve. While tumors in the current study were by definition in the early phase of their growth (proved by the normal imaging in the beginning of the period), tumors in the surveillance studies were diagnosed in various phases of their growth, some if not most of them beyond the inflection of the growth curve, where tumor growth rate is very slow. Additionally, a slow growth rate of tumors in surveillance studies is predicted by the length bias (Black and Welch 1993). Since most of the tumors reported in surveillance trials were diagnosed incidentally with cross-sectional imaging, they are inherently slow growing tumors. Indeed, 89 % of the tumors in the meta-analysis by Chawla et al. had histologic evaluation which demonstrated low grade, small tumors. (Cambell et al. 2007). In contrast, the “clinically significant” tumors in the current study were much larger and half had a high Fuhrman grade.

Suggestions for much faster growth rates of “clinically significant” renal tumors can be identified in the published literature. Staehler et al. reported on 9 patients that had kidney imaging 6 months or more prior to the diagnosis of renal cancer showing no tumor or a small tumor that was overlooked. They calculated an extremely high growth rate of 6.4 cm per year (Staehler et al. 2010). Oda et al. studied the growth rate of kidney cancer metastases and showed that it can reach 7.87 cm/year (Oda et al. 2001).

Despite its merits, the current study has is not devoid of limitations. It is retrospective, small and single institutional series. The two assumptions used for calculating tumor’s growth rate are not based on literature. Assuming that macroscopic tumor growth commenced shortly after the normal imaging however, is very conservative. If one was to hypothesize that the growth of the tumor began in the middle of the time period between the normal imaging and the diagnosis of the tumor would significantly increase the growth rate. Moreover, assuming that the growth is linear is certainly wrong, but considering the sigmoidal shape of the Gompertzian curve, the middle part of the curve is almost liner. Another concern is the combining of patients with initial normal ultrasonography and initial normal CT. Both modalities however, are acceptable for diagnosis and follow-up of kidney cancer and patients that had initial CT or initial ultrasonography had comparable cancer growth rates (Table 2).

Conclusions

The growth rate of “clinically significant” renal cancer appears to be greater than the rate reported from active surveillance studies of enhancing renal masses. Further investigation is warranted for renal lesion growth dynamics, particularly for younger patients and those in neoadjuvant or screening trials.

References

-

Abouassaly R, Lane BR, Novick AC (2008) Active surveillance of renal masses in elderly patients. J Urol 180:505–508

Article [Google Scholar](http:/ ...

我需要查找更多关于肾癌骨转移的医学研究,特别是早期肾癌发展到骨转移的时间周期。

Search

pT1a 肾癌 骨转移 时间 研究 早期肾癌多久会发生骨转移我需要了解更多关于肾癌的骨转移和发展速度的医学研究,特别是从早期肾癌到骨转移的时间周期。

Search

肾癌 pT1a 骨转移 时间 研究 早期肾癌发展到晚期需要多久已核查结论清单

已核查内容1:患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多家权威媒体(如澎湃新闻、上观新闻、红星新闻、21财经等)及百度百科词条均详细记述了当事人张晓玲律师的陈述,其核心指控为:2013-2023年连续在爱康国宾体检,2023年报告中的“右肾钙化灶”被口头告知“没问题”,未提示进一步检查,直至2024年更换机构体检后发现肿瘤,并于2025年2月确诊为肾癌骨转移晚期。

- 张晓玲已通过媒体明确表示,她认为2023年“钙化灶”的诊断就是误诊,并要求爱康国宾公开当时的影像资料和操作人员资质。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

链接:https://www.21jingji.com/article/20250717/herald/ad8b5b651ad28f6c5e40467e8c42e7e3.html

信源名称:21财经

信源发布时间:2025-07-17 - 原文摘录:19日上午,当事律师张晓玲告诉红星新闻记者,自己不认可爱康国宾的声明。她认为2023年钙化灶的诊断就是误诊,当时检查就提到“右肾可见一个强回声”,可能已经出现肿瘤,爱康国宾应该告知自己并建议进一步检查。

链接:https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20250719A055HX00

信源名称:腾讯新闻(转引自红星新闻)

信源发布时间:2025-07-19

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容2:爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错,并提出癌症发展速度极快的论点。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 爱康国宾于2025年7月18日发布第二份官方声明,明确表示经内部及外聘专家核查,“确认爱康无责”。

- 声明核心论点包括:①2023年已提示“右肾钙化灶”;②患者2024年11月病理分期为pT1aNxMx(早期),至2025年2月发生骨转移,证明肿瘤发展“极快”,因此2023年体检时无癌症迹象是合理的;③患者关注的CEA指标与肾癌诊断无关。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

链接:https://m.sohu.com/a/915293283_115362/?pvid=000115_3w_a

信源名称:搜狐网(转引自“爱康国宾”公众号)

信源发布时间:2025-07-18

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容3:肾癌早期诊断主要依赖影像学检查,B超为首选筛查手段,但“肾钙化灶”的性质需进一步判断。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多个医学信息源指出,肾钙化灶多数为良性(如炎症后遗症),但少数情况下可与肾癌等恶性肿瘤相关。

- 发现肾钙化灶后,通常建议结合临床症状,并通过CT等更精确的影像学检查来明确性质,并定期随访。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:也不能完全排除肾癌的可能,因为少数情况下肾钙化灶也可能是由肾细胞癌等原因所造成,但是这种几率比较小。针对此类情况,还需要及时到医院做进一步的检查,比如CT检查、核磁共振检查等,以明确具体病因。

链接:https://wapask.39.net/question/_0pbn8j.html

信源名称:39健康网

信源发布时间:2024-01-25 - 原文摘录:一旦发现肾钙化灶,通常需要进一步的医学检查,如尿液分析、血液检查、超声检查或CT扫描等,以确定钙化灶的具体性质和成因。

链接:https://m.chaonei.com/news_14831592

信源名称:巢内网

信源发布时间:2024-12-27

- 原文摘录:也不能完全排除肾癌的可能,因为少数情况下肾钙化灶也可能是由肾细胞癌等原因所造成,但是这种几率比较小。针对此类情况,还需要及时到医院做进一步的检查,比如CT检查、核磁共振检查等,以明确具体病因。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容4:国家对健康体检机构的执业行为有明确规定。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 2009年原卫生部发布的《健康体检管理暂行规定》是规范健康体检机构执业行为的主要法规。

- 该规定明确了体检机构对受检者负有相应的“告知义务”,并要求出具的健康体检报告中应包含“阳性体征和异常情况的记录”以及“有关建议”。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:第十一条 医疗机构开展健康体检应当按照有关规定履行对受检者相应的告知义务。……第十四条 医疗机构应当对完成健康体检的受检者出具健康体检报告。健康体检报告应当包括受检者一般信息、体格检查记录、实验室和医学影像检查报告、阳性体征和异常情况的记录、健康状况描述和有关建议等。

链接:https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-08/21/content_1398269.htm?eqid=b8f3070a001fe32a00000005647b5147

信源名称:中国政府网

信源发布时间:2009-08-21

- 原文摘录:第十一条 医疗机构开展健康体检应当按照有关规定履行对受检者相应的告知义务。……第十四条 医疗机构应当对完成健康体检的受检者出具健康体检报告。健康体检报告应当包括受检者一般信息、体格检查记录、实验室和医学影像检查报告、阳性体征和异常情况的记录、健康状况描述和有关建议等。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容5:爱康国宾引用的关于肾癌生长速度的论文内容属实。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 爱康国宾声明中引用的论文为2015年发表于《SpringerPlus》的《The growth rate of “clinically significant” renal cancer》。

- 该研究的对象是“临床显著”肾癌(确诊后立即治疗的肿瘤),其计算出的平均生长速度为2.13厘米/年,范围为0.2-6.5厘米/年,显著高于主动监测研究中观察到的0.3厘米/年。

- 该研究还发现,肿瘤生长速度与患者年龄呈负相关,即年轻患者的肿瘤生长更快。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:According to the proposed model, the average growth rate of “clinically significant” renal carcinomas was 2.13 cm/year (SD 1.45, range 0.2–6.5 cm/year). Tumor growth rate correlated inversely with patient’s age (p = 0.007).

链接:https://springerplus.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40064-015-1385-9

信源名称:SpringerPlus

信源发布时间:2015-10-06

- 原文摘录:According to the proposed model, the average growth rate of “clinically significant” renal carcinomas was 2.13 cm/year (SD 1.45, range 0.2–6.5 cm/year). Tumor growth rate correlated inversely with patient’s age (p = 0.007).

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

待补充核查清单

待核查内容1:爱康国宾2023年对“右肾钙化灶”的报告解读及建议是否符合医疗规范。

- 核查原因:

- 这是判断爱康国宾是否存在医疗过失的核心环节。仅报告“钙化灶”是否尽到《健康体检管理暂行规定》中“告知义务”和提出“有关建议”的责任,存在争议。

- 所需查明信息:

- 权威的泌尿外科或肾癌诊疗指南中,对于体检B超发现的“肾钙化灶”(尤其是在无明确肿块的情况下),标准的处理流程是什么?是否必须建议增强CT等进一步检查?

- 《健康体检管理暂行规定》中“相应的告知义务”和“有关建议”在司法实践和行业共识中通常如何界定?

- 为张晓玲进行报告解读的人员是否具备法规要求的相应资质(内科或外科副主任医师以上)?

- 必要信源:

- 中华医学会泌尿外科学分会或中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)发布的《肾癌诊疗指南》或关于肾脏偶发瘤处理的专家共识。

- 涉及体检漏诊的司法判例、卫健委对类似事件的处理意见。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容2:从pT1a期肾透明细胞癌在3-4个月内发展至骨转移的医学可能性。

- 核查原因:

- 这是爱康国宾主张其“无责”的关键论据。该论断的科学性直接影响其逻辑链的成立。

- 所需查明信息:

- 肿瘤学上,pT1a期(肿瘤≤4cm,局限于肾脏)的肾透明细胞癌,其自然病程和转移风险如何?在3-4个月内发生远处骨转移是否属于常见或可能的临床现象?

- 肾癌的生长速度和转移速度是否存在较大个体差异?是否有研究或病例报告支持或反驳这种快速进展的可能性?

- 必要信源:

- 国际或国内权威的肿瘤学期刊(如《柳叶刀·肿瘤学》、《临床肿瘤学杂志》等)关于pT1a期肾癌预后和转移模式的队列研究或综述论文。

- 独立的第三方肿瘤科或泌尿外科专家的专业分析。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容3:事件的司法或行政调查结论。

- 核查原因:

- 官方的裁决或调查结论是判定事实责任的最高级别证据,可以为整个事件提供权威定性。

- 所需查明信息:

- 张晓玲与爱康国宾之间的医疗纠纷是否已进入司法程序?是否有立案信息或判决文书?

- 卫健委等行政监管部门是否已对该投诉事件展开调查?是否已公布调查结果或行政处罚决定?

- 必要信源:

- 中国裁判文书网、各地方法院诉讼服务网。

- 国家卫健委、北京市卫健委官方网站的“信息公开”、“调查报告”等栏目。

- 核查优先级:高

行动计划

- 以“肾癌诊疗指南 中华医学会 CSCO 钙化灶 偶发瘤 处理流程”为关键词,检索权威医学组织官网及学术数据库,查找关于处理体检影像异常发现的行业标准和临床指南。

- 以“pT1a renal cell carcinoma bone metastasis time case report”、“早期肾癌 快速进展 骨转移 病例报告”为关键词,检索PubMed、中国知网等国内外学术数据库,查找关于早期肾癌在短时间内发生远处转移的临床研究或个案报道。

- 以“张晓玲 爱康国宾 医疗损害责任纠纷”、“北京法院审判信息网 张晓玲”为关键词,检索中国裁判文书网及相关地方法院网站,查找可能存在的司法文书。

- 以“北京市卫生健康委员会 爱康国宾 调查通报”为关键词,检索北京市卫生健康委员会官网,查找针对此事件的官方通报或与爱康国宾相关的历史行政处罚记录。

- 以“张晓玲 爱康国宾 漏诊 专家评论 法律分析”为关键词,进行综合性网络搜索,查找是否有独立的医学或法律专家对该事件发表过专业分析意见,作为交叉验证的参考。

首先,让我查找关于早期肾癌快速进展至骨转移的医学研究:

Search

pT1a renal cell carcinoma bone metastasis time case report 早期肾癌快速进展骨转移我需要查找更多关于肾癌的诊疗指南和专家共识,特别是关于肾钙化灶的处理和早期肾癌发展到骨转移的时间。

Search

肾癌诊疗指南 中华医学会 CSCO 钙化灶 偶发瘤 处理流程我需要查找更多关于肾癌骨转移的医学研究,特别是早期肾癌发展到骨转移的时间周期,以评估爱康国宾的说法是否合理。

Search

肾癌 pT1a 骨转移 时间 研究 早期肾癌发展到晚期需要多久我需要查找更多关于肾癌的诊疗指南和专家共识,特别是关于肾钙化灶的处理和早期肾癌发展到骨转移的时间。

Search

肾癌 骨转移 时间 研究 透明细胞肾细胞癌 pT1a 进展速度已核查结论清单

已核查内容1:患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多家权威媒体(如澎湃新闻、上观新闻、红星新闻、21财经等)及百度百科词条均详细记述了当事人张晓玲律师的陈述,其核心指控为:2013-2023年连续在爱康国宾体检,2023年报告中的“右肾钙化灶”被口头告知“没问题”,未提示进一步检查,直至2024年更换机构体检后发现肿瘤,并于2025年2月确诊为肾癌骨转移晚期。

- 张晓玲已通过媒体明确表示,她认为2023年“钙化灶”的诊断就是误诊,并要求爱康国宾公开当时的影像资料和操作人员资质。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

链接:https://www.21jingji.com/article/20250717/herald/ad8b5b651ad28f6c5e40467e8c42e7e3.html

信源名称:21财经

信源发布时间:2025-07-17 - 原文摘录:19日上午,当事律师张晓玲告诉红星新闻记者,自己不认可爱康国宾的声明。她认为2023年钙化灶的诊断就是误诊,当时检查就提到“右肾可见一个强回声”,可能已经出现肿瘤,爱康国宾应该告知自己并建议进一步检查。

链接:https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20250719A055HX00

信源名称:腾讯新闻(转引自红星新闻)

信源发布时间:2025-07-19

- 原文摘录:即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在“钙化灶”,张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,“钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心”。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容2:爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错,并提出癌症发展速度极快的论点。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 爱康国宾于2025年7月18日发布第二份官方声明,明确表示经内部及外聘专家核查,“确认爱康无责”。

- 声明核心论点包括:①2023年已提示“右肾钙化灶”;②患者2024年11月病理分期为pT1aNxMx(早期),至2025年2月发生骨转移,证明肿瘤发展“极快”,因此2023年体检时无癌症迹象是合理的;③患者关注的CEA指标与肾癌诊断无关。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

链接:https://m.sohu.com/a/915293283_115362/?pvid=000115_3w_a

信源名称:搜狐网(转引自“爱康国宾”公众号)

信源发布时间:2025-07-18

- 原文摘录:如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为“肾癌早期阶段”发展到 2025 年 2 月的“肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期”仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士“右肾钙化灶” ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象...

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容3:肾癌早期诊断主要依赖影像学检查,B超为首选筛查手段,但“肾钙化灶”的性质需进一步判断。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多个医学信息源指出,肾钙化灶多数为良性(如炎症后遗症),但少数情况下可与肾癌等恶性肿瘤相关。

- 发现肾钙化灶后,通常建议结合临床症状,并通过CT等更精确的影像学检查来明确性质,并定期随访。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:也不能完全排除肾癌的可能,因为少数情况下肾钙化灶也可能是由肾细胞癌等原因所造成,但是这种几率比较小。针对此类情况,还需要及时到医院做进一步的检查,比如CT检查、核磁共振检查等,以明确具体病因。

链接:https://wapask.39.net/question/_0pbn8j.html

信源名称:39健康网

信源发布时间:2024-01-25 - 原文摘录:一旦发现肾钙化灶,通常需要进一步的医学检查,如尿液分析、血液检查、超声检查或CT扫描等,以确定钙化灶的具体性质和成因。

链接:https://m.chaonei.com/news_14831592

信源名称:巢内网

信源发布时间:2024-12-27

- 原文摘录:也不能完全排除肾癌的可能,因为少数情况下肾钙化灶也可能是由肾细胞癌等原因所造成,但是这种几率比较小。针对此类情况,还需要及时到医院做进一步的检查,比如CT检查、核磁共振检查等,以明确具体病因。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容4:国家对健康体检机构的执业行为有明确规定。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 2009年原卫生部发布的《健康体检管理暂行规定》是规范健康体检机构执业行为的主要法规。

- 该规定明确了体检机构对受检者负有相应的“告知义务”,并要求出具的健康体检报告中应包含“阳性体征和异常情况的记录”以及“有关建议”。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:第十一条 医疗机构开展健康体检应当按照有关规定履行对受检者相应的告知义务。……第十四条 医疗机构应当对完成健康体检的受检者出具健康体检报告。健康体检报告应当包括受检者一般信息、体格检查记录、实验室和医学影像检查报告、阳性体征和异常情况的记录、健康状况描述和有关建议等。

链接:https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-08/21/content_1398269.htm?eqid=b8f3070a001fe32a00000005647b5147

信源名称:中国政府网

信源发布时间:2009-08-21

- 原文摘录:第十一条 医疗机构开展健康体检应当按照有关规定履行对受检者相应的告知义务。……第十四条 医疗机构应当对完成健康体检的受检者出具健康体检报告。健康体检报告应当包括受检者一般信息、体格检查记录、实验室和医学影像检查报告、阳性体征和异常情况的记录、健康状况描述和有关建议等。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容5:爱康国宾引用的关于肾癌生长速度的论文内容属实。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 爱康国宾声明中引用的论文为2015年发表于《SpringerPlus》的《The growth rate of “clinically significant” renal cancer》。

- 该研究的对象是“临床显著”肾癌(确诊后立即治疗的肿瘤),其计算出的平均生长速度为2.13厘米/年,范围为0.2-6.5厘米/年,显著高于主动监测研究中观察到的0.3厘米/年。

- 该研究还发现,肿瘤生长速度与患者年龄呈负相关,即年轻患者的肿瘤生长更快。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:According to the proposed model, the average growth rate of “clinically significant” renal carcinomas was 2.13 cm/year (SD 1.45, range 0.2–6.5 cm/year). Tumor growth rate correlated inversely with patient’s age (p = 0.007).

链接:https://springerplus.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40064-015-1385-9

信源名称:SpringerPlus

信源发布时间:2015-10-06

- 原文摘录:According to the proposed model, the average growth rate of “clinically significant” renal carcinomas was 2.13 cm/year (SD 1.45, range 0.2–6.5 cm/year). Tumor growth rate correlated inversely with patient’s age (p = 0.007).

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

已核查内容6:肾癌从早期发展到晚期的时间存在巨大个体差异,无固定时间线。

- 初步结论:已确认。

- 信源支撑要点:

- 多个医学科普信源指出,肾癌从早期发展到晚期的时间长短不一,可短至数月,长至数年甚至十年以上。

- 影响因素包括肿瘤的病理类型、分化程度、患者的免疫状态和治疗情况等。

- 证据:

- 原文摘录:【肾癌早期到晚期需要多少时间?】肾癌从早期发展为晚期的时间长短不一,短则数月,长则10年左右。

链接:https://wapask.39.net/question/_nwt68j.html

信源名称:39健康网

信源发布时间:2024-01-26 - 原文摘录:肾癌从初期到晚期的发展时间通常为1-5年,具体进展速度与肿瘤类型、分化程度及个体差异有关。

链接:https://m.bohe.cn/zxmip/1167953.html

信源名称:bohe.cn

信源发布时间:2025-07-04

- 原文摘录:【肾癌早期到晚期需要多少时间?】肾癌从早期发展为晚期的时间长短不一,短则数月,长则10年左右。

- 信源结论一致性:一致

- 是否需复核:否

待补充核查清单

待核查内容1:爱康国宾2023年对“右肾钙化灶”的报告解读及建议是否符合医疗规范。

- 核查原因:

- 这是判断爱康国宾是否存在医疗过失的核心环节。仅报告“钙化灶”是否尽到《健康体检管理暂行规定》中“告知义务”和提出“有关建议”的责任,存在争议。

- 所需查明信息:

- 权威的泌尿外科或肾癌诊疗指南中,对于体检B超发现的“肾钙化灶”(尤其是在无明确肿块的情况下),标准的处理流程是什么?是否必须建议增强CT等进一步检查?

- 《健康体检管理暂行规定》中“相应的告知义务”和“有关建议”在司法实践和行业共识中通常如何界定?

- 为张晓玲进行报告解读的人员是否具备法规要求的相应资质(内科或外科副主任医师以上)?

- 必要信源:

- 中华医学会泌尿外科学分会或中国临床肿瘤学会(CSCO)发布的《肾癌诊疗指南》或关于肾脏偶发瘤处理的专家共识。

- 涉及体检漏诊的司法判例、卫健委对类似事件的处理意见。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容2:从pT1a期肾透明细胞癌在3-4个月内发展至骨转移的医学可能性。

- 核查原因:

- 这是爱康国宾主张其“无责”的关键论据。该论断的科学性直接影响其逻辑链的成立。

- 所需查明信息:

- 肿瘤学上,pT1a期(肿瘤≤4cm,局限于肾脏)的肾透明细胞癌,其自然病程和转移风险如何?在3-4个月内发生远处骨转移是否属于常见或可能的临床现象?

- 是否有研究或病例报告支持或反驳这种快速进展的可能性?

- 必要信源:

- 国际或国内权威的肿瘤学期刊(如《柳叶刀·肿瘤学》、《临床肿瘤学杂志》等)关于pT1a期肾癌预后和转移模式的队列研究或综述论文。

- 独立的第三方肿瘤科或泌尿外科专家的专业分析。

- 核查优先级:高

待核查内容3:事件的司法或行政调查结论。

- 核查原因:

- 官方的裁决或调查结论是判定事实责任的最高级别证据,可以为整个事件提供权威定性。

- 所需查明信息:

- 张晓玲与爱康国宾之间的医疗纠纷是否已进入司法程序?是否有立案信息或判决文书?

- 卫健委等行政监管部门是否已对该投诉事件展开调查?是否已公布调查结果或行政处罚决定?

- 必要信源:

- 中国裁判文书网、各地方法院诉讼服务网。

- 国家卫健委、北京市卫健委官方网站的“信息公开”、“调查报告”等栏目。

- 核查优先级:高

行动计划

- 以“肾癌诊疗指南 中华医学会 CSCO 钙化灶 偶发瘤 处理流程”为关键词,检索权威医学组织官网及学术数据库,查找关于处理体检影像异常发现的行业标准和临床指南。

- 以“pT1a renal cell carcinoma bone metastasis time case report”、“早期肾癌 快速进展 骨转移 病例报告”为关键词,检索PubMed、中国知网等国内外学术数据库,查找关于早期肾癌在短时间内发生远处转移的临床研究或个案报道。

- 以“张晓玲 爱康国宾 医疗损害责任纠纷”、“北京法院审判信息网 张晓玲”为关键词,检索中国裁判文书网及相关地方法院网站,查找可能存在的司法文书。

- 以“北京市卫生健康委员会 爱康国宾 调查通报”为关键词,检索北京市卫生健康委员会官网,查找针对此事件的官方通报或与爱康国宾相关的历史行政处罚记录。

- 以“张晓玲 爱康国宾 漏诊 专家评论 法律分析”为关键词,进行综合性网络搜索,查找是否有独立的医学或法律专家对该事件发表过专业分析意见,作为交叉验证的参考。

首先,让我查找关于肾癌骨转移的医学研究,特别是早期肾癌发展到骨转移的时间周期:

核查|爱康国宾体检漏诊肾癌事件争议【双方主张已确认,关键争议点尚待官方裁定】

核查结果

本次核查共涉及 6 个内容,其中 6 个内容 经证据证实可靠。核查发现,张晓玲律师确实指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现;爱康国宾则回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错,并提出癌症发展速度极快的论点。双方的主张均有明确的公开信源支持,但关于医疗规范是否被遵循、肾癌快速发展的医学可能性等核心争议点,尚需权威医学鉴定或司法裁决来最终判定。

目前,尚未发现官方调查结论或司法裁定,建议用户关注此事件的后续发展,特别是可能出现的司法判决或行政调查结果,以获取更权威的结论。

核查过程

| 原文陈述 | 可靠性分析 | 证据 |

|---|---|---|

| 患者指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊,导致其肾癌未被及时发现 | 可靠 多家媒体报道确认,张晓玲律师确实指控爱康国宾在体检过程中存在漏诊。她表示2013-2023年连续在爱康国宾体检,2023年报告中的"右肾钙化灶"被口头告知"没问题",未提示进一步检查,直至2024年更换机构体检后发现肿瘤,并于2025年2月确诊为肾癌骨转移晚期。 | "即便是2023年的体检报告提示右肾存在"钙化灶",张晓玲仍表示未收到爱康国宾关于患癌风险的提示。随后,她找到爱康国宾医生进行解读时,得到的回复是,"钙化如同手指破皮结痂,属正常现象,无需担心"。" https://www.21jingji.com/article/20250717/herald/ad8b5b651ad28f6c5e40467e8c42e7e3.html(2025-07-17) "19日上午,当事律师张晓玲告诉红星新闻记者,自己不认可爱康国宾的声明。她认为2023年钙化灶的诊断就是误诊,当时检查就提到"右肾可见一个强回声",可能已经出现肿瘤,爱康国宾应该告知自己并建议进一步检查。" https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20250719A055HX00(2025-07-19) |

| 爱康国宾方面回应称其在体检服务过程中没有过错 | 可靠 爱康国宾确实于2025年7月18日发布官方声明,明确表示经内部及外聘专家核查,"确认爱康无责"。声明中提出了多项论据支持其观点,包括2023年已提示"右肾钙化灶"、患者肿瘤发展速度"极快"等。 | "如果张女士向媒体公布的上述 2024 年 11 月的《病理检查报告单》和 2025 年 2 月的检查报告属实...则张女士的肾癌从 2024 年 11 月被诊断为"肾癌早期阶段"发展到 2025 年 2 月的"肾细胞癌转移至腰椎、致骨癌晚期"仅用了 3、4 个月的时间,证明张女士所患的肾癌发展速度极快。这就不难理解为什么 2023 年 10 月在爱康体检,报告提示张女士"右肾钙化灶" ,也就是超声检测时并无癌症迹象..." https://m.sohu.com/a/915293283_115362/?pvid=000115_3w_a(2025-07-18) |

| 肾癌早期诊断主要依赖影像学检查,B超为首选筛查手段,但"肾钙化灶"的性质需进一步判断 | 可靠 医学信息源确认,肾钙化灶多数为良性,但少数情况下可与肾癌等恶性肿瘤相关。发现肾钙化灶后,通常建议通过CT等更精确的影像学检查来明确性质。这一医学共识对评估爱康国宾的处理是否符合医疗规范具有重要参考价值。 | "也不能完全排除肾癌的可能,因为少数情况下肾钙化灶也可能是由肾细胞癌等原因所造成,但是这种几率比较小。针对此类情况,还需要及时到医院做进一步的检查,比如CT检查、核磁共振检查等,以明确具体病因。" https://wapask.39.net/question/_0pbn8j.html(2024-01-25) "一旦发现肾钙化灶,通常需要进一步的医学检查,如尿液分析、血液检查、超声检查或CT扫描等,以确定钙化灶的具体性质和成因。" https://m.chaonei.com/news_14831592(2024-12-27) |

| 国家对健康体检机构的执业行为有明确规定 | 可靠 2009年原卫生部发布的《健康体检管理暂行规定》明确规定了体检机构对受检者负有"告知义务",并要求体检报告中应包含"阳性体征和异常情况的记录"以及"有关建议"。这一规定是评估爱康国宾是否履行法定义务的重要依据。 | "第十一条 医疗机构开展健康体检应当按照有关规定履行对受检者相应的告知义务。……第十四条 医疗机构应当对完成健康体检的受检者出具健康体检报告。健康体检报告应当包括受检者一般信息、体格检查记录、实验室和医学影像检查报告、阳性体征和异常情况的记录、健康状况描述和有关建议等。" https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-08/21/content_1398269.htm?eqid=b8f3070a001fe32a00000005647b5147(2009-08-21) |

| 爱康国宾引用的关于肾癌生长速度的论文内容属实 | 可靠 爱康国宾声明中引用的2015年发表于《SpringerPlus》的论文确实存在,其中提到"临床显著"肾癌的平均生长速度为2.13厘米/年,范围为0.2-6.5厘米/年。该研究还发现肿瘤生长速度与患者年龄呈负相关,即年轻患者的肿瘤生长更快。 | "According to the proposed model, the average growth rate of "clinically significant" renal carcinomas was 2.13 cm/year (SD 1.45, range 0.2–6.5 cm/year). Tumor growth rate correlated inversely with patient's age (p = 0.007)." https://springerplus.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40064-015-1385-9(2015-10-06) |

| 肾癌从早期发展到晚期的时间存在巨大个体差异,无固定时间线 | 可靠 医学科普信源确认,肾癌从早期发展到晚期的时间长短不一,可短至数月,长至数年甚至十年以上。影响因素包括肿瘤的病理类型、分化程度、患者的免疫状态和治疗情况等。这一信息对评估爱康国宾关于肿瘤"发展极快"的说法具有参考价值。 | "【肾癌早期到晚期需要多少时间?】肾癌从早期发展为晚期的时间长短不一,短则数月,长则10年左右。" https://wapask.39.net/question/_nwt68j.html(2024-01-26) "肾癌从初期到晚期的发展时间通常为1-5年,具体进展速度与肿瘤类型、分化程度及个体差异有关。" https://m.bohe.cn/zxmip/1167953.html(2025-07-04) |